Bio

Bio

I was born on November 11, 1926. A lot happened that year. Al Smith was elected governor of New York, and many people hoped he might become the first Catholic President of the United States. In Germany, a man named Paul Joseph Goebbels was appointed head of the Berlin branch of a nondescript political group, the Nazi Party. In Italy, dictator Benito Mussolini brought back capital punishment. Henry Ford set the price of his Model T at $350, and people were buzzing about the first moving pictures with sound-- "talkies." The average annual income in America was $1,313. Bread was nine cents a loaf, and a gallon of gas cost a dime.

In a flat on Providence Street in Worcester, Massachusetts, on Armistice Day, Robert Gordon's wife, Rose, gave birth at home to their second child. I was called Noah in memory of my mother's father, Noah Melnikoff, who had died only a few months before. He had been a bookbinder and, by all accounts, a wonderful man. His widow, my grandmother, Sarah Melnikoff, lived with my family for the next 35 years and was like a second mother to me.

I grew up in a working-class neighborhood of Worcester. I was a student at Grafton Street Junior High School, and 15 years old, when the United States entered the war. I remember being certain the combat would be over before I was old enough to be in it. But one year of slaughter passed . . . and another . . . and another . . . and the fighting still raged in February of 1945, when I was graduated from Classical High School.

I wanted to serve in the Navy, but I wore glasses and was color-blind. I had heard that if someone volunteered for the draft, he could choose to serve in the Navy. So I volunteered—and within a few days I was in the United States Infantry.

After basic training in Company A of the 26th Infantry Training Battalion at Camp Croft, South Carolina, I was sent to "the repple depple," Replacement Depot #2 at Fort Ord, California. We were given salt water soap and full field packs, and marched to busses while the band played; but instead of carrying us to ships, the busses took us to the Presidio of Monterey. I learned later that we had been destined to join JASCOs (Joint Assault Signal Companies), made up of Infantry trained to give covering fire while men of the Signal Corps set up first communications during the early waves of invasions. The United States was preparing to invade Japan. But suddenly brand-new weapons ("What's an atom bomb?") were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and the war was over. I finished my service unheroically as an Army clerk in a boring job in San Francisco, grateful that I had survived, grateful that I had never had to kill a human being.

Along with millions of other new civilians, I was thankful for the GI Bill and went to college. My parents, who could not have afforded medical school tuitions, nevertheless pressured me to study medicine. The medical profession represented the kind of financial security my family had never had, and it wasn't lost on them that in some death camps doctors had been the last Jews to be sent to the gas chambers. I actually tried a pre-medical course for one semester, and then changed my major to journalism without telling my mother or my father. Ever since childhood I had nursed two ambitions of my own. I wanted to be a newspaperman, and I yearned to write the kind of novels that made me love books. Halfway through journalism school at Boston University I met an undergraduate at Clark University named Lorraine Seay. The world was never the same.

In 1950 I received a Bachelor of Science in Journalism degree. The following year I earned an M.A. in English and Creative Writing from the Graduate School at Boston University, and Lorraine received her Bachelor of Arts degree in German from Clark. I went to New York and got a job as a junior editor in the periodicals department of the Avon Publishing Co., and we were married. I worked at Avon for two years and then on a small-size news and picture magazine called Focus.

We thought it was romantic that we lived with packing-case furniture in a tiny attic in Brooklyn, like poets in a Paris garret. But when our first child was born we began to yearn for home, and we returned to Massachusetts.

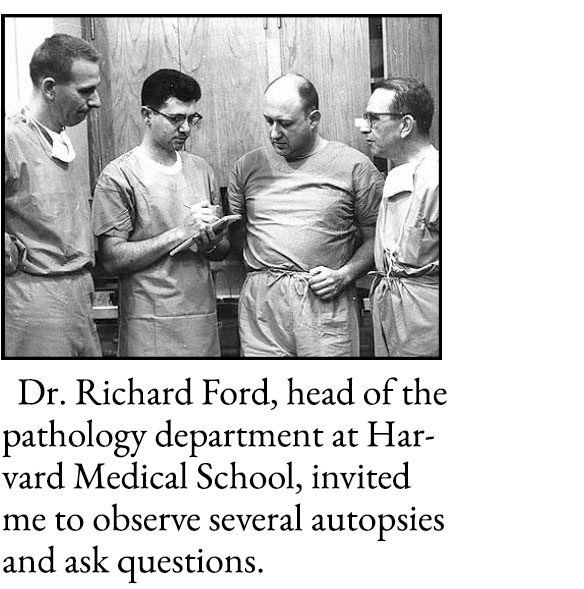

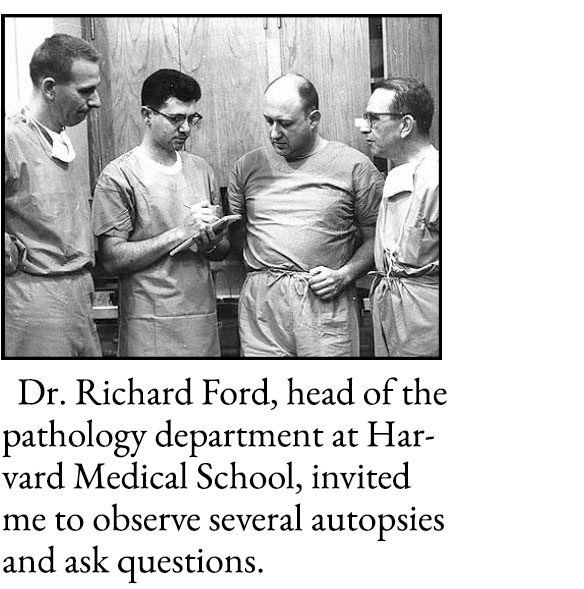

After a year of trying to make it as a freelancer, I went to work as a reporter on my hometown newspaper, The Worcester Telegram. It was the beginning of a lifetime of job satisfaction. In 1959 I was hired by The (old, broad-sheet) Boston Herald, which was a morning newspaper, like the Telegram. For a time, I was a general assignment reporter, but it was the start of an era of great scientific and medical advancement, and I began to dream up assignments in those fields. Dr. Richard Ford, head of the pathology department at Harvard Medical School, invited me to observe several autopsies and ask questions, and then I graduated to scrubbing up and standing next to surgeons who were cutting living patients. During my time at The Herald I also served as editor of The Journal of Abdominal Surgery. Within a short time, I was appointed The Herald's science editor.

I published two paperback novels about nursing, one of which became a back-of-the-book novel in Redbook Magazine, and I also began to write freelance scientific and medical articles, selling to The Saturday Evening Post, Coronet, The Saturday Review, The Reporter, Medical World News, Medical Tribune and other periodicals.

I had never lost my dream of becoming a more serious novelist. I wrote an outline for a novel and gave it to Patricia Schartle, my literary agent. To my delight and terror, she came back to me with a contract from a book publisher. It offered meager financial support for a year and brought Lorraine and me face to face with a difficult decision. By that time our marriage had been blessed with three wonderful children. We had mortgage payments, car payments, and our kids needed the usual—food, clothing, lessons, Hebrew School, orthodontia—what Zorba the Greek would have called "the whole catastrophe." But then, as now, Lorraine proved to be a writer's wife. "If you want it," she said, "do it.

We were both nervous when I signed the contract. Just before I left the newspaper, I was on jury duty when the city desk called me at the Cambridge court house and told me that Dr. Harry Solomon was trying to reach me. Dr. Solomon--Massachusetts Commissioner of Mental Health, former chair of the psychiatry department at Harvard Medical School and past president of the American Psychiatric Association--had won a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health to establish a discussion journal in the field of psychiatry, and he invited me to participate as editor. He was a warm and brilliant man; he reminded me of what my father might have been like with a formal education. I jumped at the chance to work with him, and so I began to put out Psychiatric Opinion while writing The Rabbi.

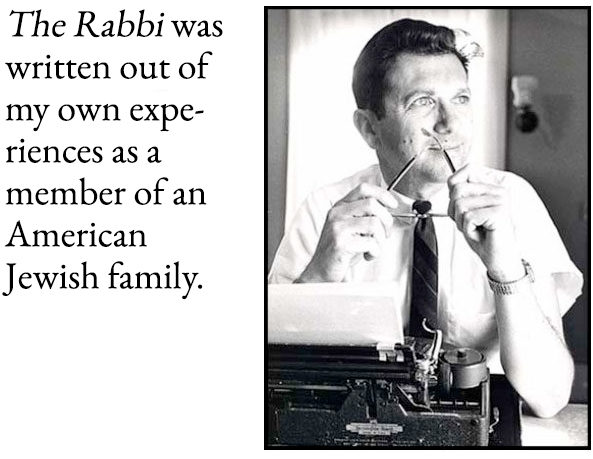

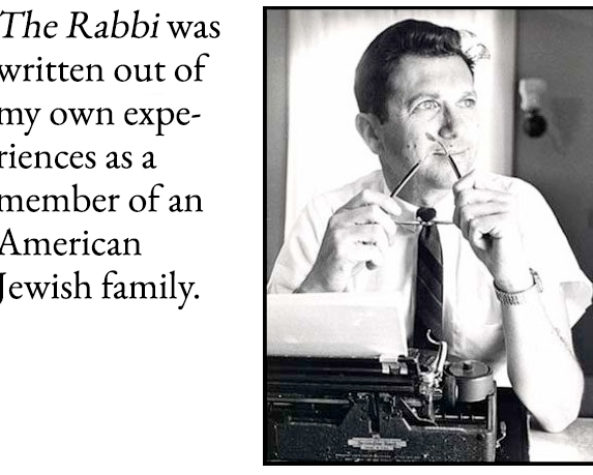

The Rabbi, written out of my own experiences as a member of an American Jewish family, garnered wonderful reviews and was on The New York Times bestseller list for 26 weeks. My second book was The Death Committee, about the formative years of three young doctors in a Boston teaching hospital. To research it, I attended mortality conferences at two leading Boston hospitals.

After several years of publishing Psychiatric Opinion, I was asked to found and publish a hard-data research journal in the field of human stress. I formed a blue-ribbon international editorial board of renowned bench scientists and published The Journal of Human Stress. Before long, I realized that I was suffering from a plethora of opportunity. I enjoyed publishing the two journals, but they were keeping me from writing novels, so in 1975 my wife began to shoulder much of the burden of journal publishing, freeing me to write The Jerusalem Diamond, the story of a gemstone and the people whose lives it affected.

Our home in Framingham allowed me two avocations that gave me great pleasure when I wasn't writing. The Sudbury River, with its beautiful trout, was only minutes away. And I became a dedicated gardener. Our house was built on good soil that once had been an apple orchard. I remembered the pleasures my family had derived during World War II from my father's Victory Garden in the field behind our house on Houghton Street in Worcester. My garden in Framingham grew larger every year.

When our youngest child began making college plans, I said to Lorraine, "How would you like to live in the country?" I was astounded when she agreed. The "country" we settled on was "forty-six acres, more or less" in the pretty little hilltown of Ashfield, Massachusetts. The land included an open hilly pasture and an adjoining cornfield that our neighbor agreed to plant as a meadow. The remainder was deep woods with half a mile of the cold, feisty, trout-filled Bear River running through it. I got in enough fishing in the stony river to keep me happy.

Our house was built facing the meadow, with its rear tucked into woods that protected it from the north and the west. I planted a mixed fruit orchard, a vegetable garden, flowers. Our neighbor made hay in the meadow several times each summer. And Lorraine and I turned the pasture into a planting of Christmas trees.

We saw wildlife very frequently, close to the house—bears, wild turkeys, bobcats, lots of deer (two bucks fought next to the garden one fall, a doe dropped a fawn in the pasture one spring). Our nephew, a professional forester, built a wonderful walking trail in a circle, along the river and through the woods, including wooden bridges over brooks and benches made of rocks and tree trunks. The trail went past a beaver pond. I kept a plastic chair in a stand of brush on the pond shore and spent many wonderful hours sitting there and watching beaver, water fowl, and two enormous snapping turtles.

We loved Ashfield. I worked in a writing space above our garage, with a view of the mountains. I was a volunteer EMT in the town's free ambulance service and served on the library board. Lorraine served several terms as Town Clerk, edited the town newspaper, and took up a craft, learning to weave baskets of ash splints the way Native Americans used to weave them.

Ashfield was a peaceful environment in which to write. I outlined and then wrote a trilogy that would follow different generations of the Cole family, a dynasty of physicians dating back to the eleventh century. The first book of The Cole Trilogy was The Physician, which follows Robert Jeremy Cole from his boyhood in England, through Europe to an Arab medical school in Persia, and beyond. The second novel of the series was Shaman, in which Robert Judson Cole goes from his native Scotland into the American frontier, where he must deal with depravations against the Indians, and the American Civil War. In the third book of the trilogy, Matters of Choice, Dr. Roberta Cole struggles to find her way through the pitfalls and challenges that every young doctor must face today.

I like to think that I came of age as a storyteller with my fourth book, The Physician. There was bad luck in its American publication; my editor left at the worst possible moment to become editor-in-chief at another publishing house. I had always heard that it is terrible for an author to become "an orphan" in this way, but I never had believed it, thinking that a good book would find its own success. The Physician sold 10,000 hard cover copies in America, a disastrous showing for a commercial novel. And I was heartbroken.

Enter, perhaps a year later, a publisher from Germany named Karl H. Blessing. He read the book in New York, loved it, and bought it. He made certain that every clerk in every book store in Germany received a reading copy, and the result was a publishing phenomenon in that country, where sales of The Physician have topped eight million copies. At the same time, a similar phenomenon was occurring in Spain, and as news from both these countries reached publishers all over Europe, they flocked to buy the book. Love for The Physician has resulted in bestsellerdom in many countries for every one of the eight books I have written. This has meant that I have had the pleasure of a number of trips to Europe, including visits to book fairs.

I wrote The Physician using only library research. For my last two books, The Last Jew and The Winemaker, I was fortunate enough to be able to make several trips to Spain. The steep, narrow streets of old Girona have changed little since the Middle Ages. In Toledo, it helped a lot to visit the exact locations I was writing about.

When I was a youth dreaming of becoming a writer, somehow old age never entered the equations of my dreams. At the age of 92, I feel that I'm still evolving as a teller of stories.

In 1995 my wife and I left the Berkshire Hills we loved and moved back to the Boston area. For a time we thought we'd keep the Ashfield place as a summer house, but it's a property that needs love and tending by live-in owners, so we sold it to people who could give it that.

When I was a youth dreaming of becoming a writer, somehow old age never entered the equations of my dreams. I now have the special pleasure of seeing my work adapted by several venues of the stage and screen.

I think a writer's existence almost always guarantees at least some hard times, and Lorraine and I have had our share; but I am fortunate to have found my greatest acceptance as a writer late in my life, when I can appreciate it fully. I've been singularly blessed with my family and friends. My youthful wishing was for a life of newspapering and book writing, and that is exactly what it has been.

Each morning I go to my computer in anticipation of the emails I receive from readers in many countries. I am grateful to every reader, for enabling me to spend my life as a scribbler of tales.

I was born on November 11, 1926. A lot happened that year. Al Smith was elected governor of New York, and many people hoped he might become the first Catholic President of the United States. In Germany, a man named Paul Joseph Goebbels was appointed head of the Berlin branch of a nondescript political group, the Nazi Party. In Italy, dictator Benito Mussolini brought back capital punishment. Henry Ford set the price of his Model T at $350, and people were buzzing about the first moving pictures with sound-- "talkies." The average annual income in America was $1,313. Bread was nine cents a loaf, and a gallon of gas cost a dime.

In a flat on Providence Street in Worcester, Massachusetts, on Armistice Day, Robert Gordon's wife, Rose, gave birth at home to their second child. I was called Noah in memory of my mother's father, Noah Melnikoff, who had died only a few months before. He had been a bookbinder and, by all accounts, a wonderful man. His widow, my grandmother, Sarah Melnikoff, lived with my family for the next 35 years and was like a second mother to me.

I grew up in a working-class neighborhood of Worcester. I was a student at Grafton Street Junior High School, and 15 years old, when the United States entered the war. I remember being certain the combat would be over before I was old enough to be in it. But one year of slaughter passed . . . and another . . . and another . . . and the fighting still raged in February of 1945, when I was graduated from Classical High School.

I wanted to serve in the Navy, but I wore glasses and was color-blind. I had heard that if someone volunteered for the draft, he could choose to serve in the Navy. So I volunteered—and within a few days I was in the United States Infantry.

After basic training in Company A of the 26th Infantry Training Battalion at Camp Croft, South Carolina, I was sent to "the repple depple," Replacement Depot #2 at Fort Ord, California. We were given salt water soap and full field packs, and marched to busses while the band played; but instead of carrying us to ships, the busses took us to the Presidio of Monterey. I learned later that we had been destined to join JASCOs (Joint Assault Signal Companies), made up of Infantry trained to give covering fire while men of the Signal Corps set up first communications during the early waves of invasions. The United States was preparing to invade Japan. But suddenly brand-new weapons ("What's an atom bomb?") were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and the war was over. I finished my service unheroically as an Army clerk in a boring job in San Francisco, grateful that I had survived, grateful that I had never had to kill a human being.

Along with millions of other new civilians, I was thankful for the GI Bill and went to college. My parents, who could not have afforded medical school tuitions, nevertheless pressured me to study medicine. The medical profession represented the kind of financial security my family had never had, and it wasn't lost on them that in some death camps doctors had been the last Jews to be sent to the gas chambers. I actually tried a pre-medical course for one semester, and then changed my major to journalism without telling my mother or my father. Ever since childhood I had nursed two ambitions of my own. I wanted to be a newspaperman, and I yearned to write the kind of novels that made me love books. Halfway through journalism school at Boston University I met an undergraduate at Clark University named Lorraine Seay. The world was never the same.

In 1950 I received a Bachelor of Science in Journalism degree. The following year I earned an M.A. in English and Creative Writing from the Graduate School at Boston University, and Lorraine received her Bachelor of Arts degree in German from Clark. I went to New York and got a job as a junior editor in the periodicals department of the Avon Publishing Co., and we were married. I worked at Avon for two years and then on a small-size news and picture magazine called Focus.

We thought it was romantic that we lived with packing-case furniture in a tiny attic in Brooklyn, like poets in a Paris garret. But when our first child was born we began to yearn for home, and we returned to Massachusetts.

After a year of trying to make it as a freelancer, I went to work as a reporter on my hometown newspaper, The Worcester Telegram. It was the beginning of a lifetime of job satisfaction. In 1959 I was hired by The (old, broad-sheet) Boston Herald, which was a morning newspaper, like the Telegram. For a time, I was a general assignment reporter, but it was the start of an era of great scientific and medical advancement, and I began to dream up assignments in those fields. Dr. Richard Ford, head of the pathology department at Harvard Medical School, invited me to observe several autopsies and ask questions, and then I graduated to scrubbing up and standing next to surgeons who were cutting living patients. During my time at The Herald I also served as editor of The Journal of Abdominal Surgery. Within a short time, I was appointed The Herald's science editor.

I published two paperback novels about nursing, one of which became a back-of-the-book novel in Redbook Magazine, and I also began to write freelance scientific and medical articles, selling to The Saturday Evening Post, Coronet, The Saturday Review, The Reporter, Medical World News, Medical Tribune, and other periodicals.

I had never lost my dream of becoming a more serious novelist. I wrote an outline for a novel and gave it to Patricia Schartle, my literary agent. To my delight and terror, she came back to me with a contract from a book publisher. It offered meager financial support for a year and brought Lorraine and me face to face with a difficult decision. By that time our marriage had been blessed with three wonderful children. We had mortgage payments, car payments, and our kids needed the usual—food, clothing, lessons, Hebrew School, orthodontia—what Zorba the Greek would have called "the whole catastrophe." But then, as now, Lorraine proved to be a writer's wife. "If you want it," she said, "do it.

We were both nervous when I signed the contract. Just before I left the newspaper, I was on jury duty when the city desk called me at the Cambridge court house and told me that Dr. Harry Solomon was trying to reach me. Dr. Solomon--Massachusetts Commissioner of Mental Health, former chair of the psychiatry department at Harvard Medical School and past president of the American Psychiatric Association--had won a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health to establish a discussion journal in the field of psychiatry, and he invited me to participate as editor. He was a warm and brilliant man; he reminded me of what my father might have been like with a formal education. I jumped at the chance to work with him, and so I began to put out Psychiatric Opinion while writing The Rabbi.

The Rabbi, written out of my own experiences as a member of an American Jewish family, garnered wonderful reviews and was on The New York Times bestseller list for 26 weeks. My second book was The Death Committee, about the formative years of three young doctors in a Boston teaching hospital. To research it, I attended mortality conferences at two leading Boston hospitals.

After several years of publishing Psychiatric Opinion, I was asked to found and publish a hard-data research journal in the field of human stress. I formed a blue-ribbon international editorial board of renowned bench scientists and published The Journal of Human Stress. Before long, I realized that I was suffering from a plethora of opportunity. I enjoyed publishing the two journals, but they were keeping me from writing novels, so in 1975 my wife began to shoulder much of the burden of journal publishing, freeing me to write The Jerusalem Diamond, the story of a gemstone and the people whose lives it affected.

Our home in Framingham allowed me two avocations that gave me great pleasure when I wasn't writing. The Sudbury River, with its beautiful trout, was only minutes away. And I became a dedicated gardener. Our house was built on good soil that once had been an apple orchard. I remembered the pleasures my family had derived during World War II from my father's Victory Garden in the field behind our house on Houghton Street in Worcester. My garden in Framingham grew larger every year.

When our youngest child began making college plans, I said to Lorraine, "How would you like to live in the country?" I was astounded when she agreed. The "country" we settled on was "forty-six acres, more or less" in the pretty little hilltown of Ashfield, Massachusetts. The land included an open hilly pasture and an adjoining cornfield that our neighbor agreed to plant as a meadow. The remainder was deep woods with half a mile of the cold, feisty, trout-filled Bear River running through it. I got in enough fishing in the stony river to keep me happy.

Our house was built facing the meadow, with its rear tucked into woods that protected it from the north and the west. I planted a mixed fruit orchard, a vegetable garden, flowers. Our neighbor made hay in the meadow several times each summer. And Lorraine and I turned the pasture into a planting of Christmas trees.

We saw wildlife very frequently, close to the house—bears, wild turkeys, bobcats, lots of deer (two bucks fought next to the garden one fall, a doe dropped a fawn in the pasture one spring). Our nephew, a professional forester, built a wonderful walking trail in a circle, along the river and through the woods, including wooden bridges over brooks and benches made of rocks and tree trunks. The trail went past a beaver pond. I kept a plastic chair in a stand of brush on the pond shore and spent many wonderful hours sitting there and watching beaver, water fowl, and two enormous snapping turtles.

We loved Ashfield. I worked in a writing space above our garage, with a view of the mountains. I was a volunteer EMT in the town's free ambulance service and served on the library board. Lorraine served several terms as Town Clerk, edited the town newspaper, and took up a craft, learning to weave baskets of ash splints the way Native Americans used to weave them.

Ashfield was a peaceful environment in which to write. I outlined and then wrote a trilogy that would follow different generations of the Cole family, a dynasty of physicians dating back to the eleventh century. The first book of The Cole Trilogy was The Physician, which follows Robert Jeremy Cole from his boyhood in England, through Europe to an Arab medical school in Persia, and beyond. The second novel of the series was Shaman, in which Robert Judson Cole goes from his native Scotland into the American frontier, where he must deal with depravations against the Indians, and the American Civil War. In the third book of the trilogy, Matters of Choice, Dr. Roberta Cole struggles to find her way through the pitfalls and challenges that every young doctor must face today.

I like to think that I came of age as a storyteller with my fourth book, The Physician. There was bad luck in its American publication; my editor left at the worst possible moment to become editor-in-chief at another publishing house. I had always heard that it is terrible for an author to become "an orphan" in this way, but I never had believed it, thinking that a good book would find its own success. The Physician sold 10,000 hard cover copies in America, a disastrous showing for a commercial novel. And I was heartbroken.

Enter, perhaps a year later, a publisher from Germany named Karl H. Blessing. He read the book in New York, loved it, and bought it. He made certain that every clerk in every book store in Germany received a reading copy, and the result was a publishing phenomenon in that country, where sales of The Physician have topped eight million copies. At the same time, a similar phenomenon was occurring in Spain, and as news from both these countries reached publishers all over Europe, they flocked to buy the book. Love for The Physician has resulted in bestsellerdom in many countries for every one of the eight books I have written. This has meant that I have had the pleasure of a number of trips to Europe, including visits to book fairs.

I wrote The Physician using only library research. For my last two books, The Last Jew and The Winemaker, I was fortunate enough to be able to make several trips to Spain. The steep, narrow streets of old Girona have changed little since the Middle Ages. In Toledo, it helped a lot to visit the exact locations I was writing about.

When I was a youth dreaming of becoming a writer, somehow old age never entered the equations of my dreams. At the age of 92, I feel that I'm still evolving as a teller of stories.

In 1995 my wife and I left the Berkshire Hills we loved and moved back to the Boston area. For a time we thought we'd keep the Ashfield place as a summer house, but it's a property that needs love and tending by live-in owners, so we sold it to people who could give it that.

When I was a youth dreaming of becoming a writer, somehow old age never entered the equations of my dreams. I now have the special pleasure of seeing my work adapted by several venues of the stage and screen.

I think a writer's existence almost always guarantees at least some hard times, and Lorraine and I have had our share; but I am fortunate to have found my greatest acceptance as a writer late in my life, when I can appreciate it fully. I've been singularly blessed with my family and friends. My youthful wishing was for a life of newspapering and book writing, and that is exactly what it has been.

Each morning I go to my computer in anticipation of the emails I receive from readers in many countries. I am grateful to every reader, for enabling me to spend my life as a scribbler of tales.